ARTICLE: Ben Freeman: Romance

copyright Ben Freeman, courtesy of Westwood Gallery New York.

copyright Ben Freeman, courtesy of Westwood Gallery New York.

Photography, by its nature, has been an able documentary vehicle. However, since its genesis, artists have been driven to explore and develop the evocative properties of the photographic image. In a sense, this has been a quest to see if within photography'sfundamental realism lay the potential to express something without explicitly stating it, in a similar fashion that the measured cesura in music creates a space that speaks as eloquently as the notes on either side of that pause.

Almost as soon as photography was invented in 1839, its practitioners were drawn to the concept of combining pictures to create a more meaningful image. In the 1850s, Gustave Le Gray pieced together majestic seascapes by printing from one negative for the detailed foreground and from another for the sweeping sky in the background. Later, in the 1920s, Alexander Rodchenko, foremost among the Russian Constructivists, incorporated multiple images from a wide variety of sources for his work. In Germany, artists like Herbert Bayer collaged images to surrealist effect, while in the 1940s, John Heartfield made jarring pieces that critiqued the Nazi regime through the use of fragmented imagery. Contemporary artists like Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince combine multiple found images overlaid, in the case of Kruger, with text, to comment on the commercialization and commodification of our culture.

Most of this work could be characterized as having a directness that suggests the artist is concerned primarily with communicating his or her message. While all work involves some kind of dialogue between the artist and the viewer, these are not pieces that readily lend themselves to personal interpretation.

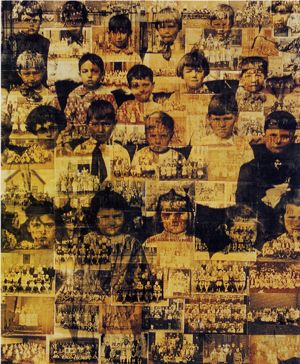

However, in the art of Ben Freeman, something different is at hand. Freeman's work is an amalgam of techniques, initiated by collaging layers of different elements, such as 19th century photographs or documents, and then overlaying them with projected imagery. As with many contemporary artists, Freeman's art operates on multiple levels. On the one, process is integral to the art (in the same way that Damian Hirst's shark, floating in a tank, is, to a degree, about the very physicality of a shark, floating in a tank). Thus, Freeman's complex methodology is an essential ingredient in creating an art object. But on another level, it is also clearly a process for grappling with important ideas and emotions. Freeman's work becomes a Proustian experience, allowing the viewer to travel along a journey of souvenirs and memories spanning centuries and generations.

The use of old pictures and vintage portraits serves as a memorial to a time gone by. There is something inherently nostalgic and unabashedly romantic about looking at these images. The fact that they are anonymous allows each viewer to imbue them with their own meaning. Unlike those other artists employing multiple imagery in their work, Freeman's pieces are not just about the place they claim, but also about the space they suggest. These pictures are questions posed, and left unanswered. The layering of the imagery gives them, literally, an aura of transparency and, consequently, a fleeting, transitory quality.

Freeman's art seems to forge a temporal bridge, between the present moment and the past. These reliquary pieces have a connotative quality that is mutable, though, whereby the meaning and significance of each piece is dependent on the viewer's relationship to the work as much, if not more, than the artist's. There is also something self-referential in this work, in the sense that it is founded on the acknowledgement of the emotional potency that photographic images have on us today. The 19th century portrait, in its day, never had this many layers of information attached to it, but Freeman's portraits cannot exist in theirmoment without being self-aware of the power that the photographic image holds as a repository of feelings. In this regard, Freeman's art is like both the strong chords struck on a piano during a concerto, and the moment just after the fingers have come off the keys, when the memory of the sound still reverberates through the hall.

2000